How Fascism Doesn’t Work

No, Just Because You Disagree With Your Political Opponents It Doesn’t Mean They’re Fascists

In How Fascism Works: The Politics of Us and Them, Yale University philosopher Jason Stanley attempts to identify what he calls fascist politics. But I will cut straight to the chase and assert that the book doesn’t deliver on what it advertises. The main problem with the book is that Stanley seems to be saying that mainstream conservative political views are, in fact, just tantamount to “fascist politics”. This is analogous to claiming that mainstream political views held by Democrats, and even progressives, are, in fact, just tantamount to “communism” or “Marxism”—or that such views are anti-American. But neither of these claims is accurate—what these kinds of claims amount to are rhetorical slanders that try to taint disfavored political views with highly charged labels. It’s unfortunate and disappointing to see this kind of language used in a book by an academic philosopher.

There are many people who, for instance, champion merit and free expression, prefer secure borders and legal immigration, reject the intrusion of trans-women into women’s spaces, do not think that America is a white supremacy, and who think that universities are bastions of political intolerance and have been corrupted by the discriminatory and authoritative ideology dubbed Diversity, Inclusion, and Equity. But if you read Stanley’s book, you may certainly get the impression that having these political views makes you a fascist—or at least an advocate of fascist politics. Which is absurd. And thus, I concur with the philosopher Peter Ludlow’s claim in his review of Stanley’s book that Stanley conflates these mainstream and common views with fascism—which many liberals and moderates hold, in addition to many conservatives.

Stanley interprets a couple of quotes from 1922 by Mussolini as if Mussolini was advocating for a return to a past golden age. Stanley believes that nostalgically hankering for a past age is a marker of fascist politics. But as Ludlow points out, the problem with this interpretation is that it is not what Mussolini was actually advocating for in the quoted speeches. What Mussolini was advocating in one those speeches was a goal for the future—a lodestar by which to orient the nation. In the other speech, he did not actually advocate for a return to a golden age of Rome, but rather for something more specific, namely that the army try to emulate the discipline of the Roman army. As Ludlow puts it:

“None of this is to say that fascists never make use of myths about a better, shinier, past, but often these appeals to the past are pragmatic rather than essential to fascism’s methods (that is, to “how fascism works”).”

“Was patriarchy an outgrowth of fascism or was Mussolini securing power in a place that was already hyper-patriarchal? Under the Pisanelli Code, in effect prior to Mussolini, women were denied the right to vote and the right to hold public office. By contrast the initial fascist platform promised suffrage to women (before voting became moot).”

“Perhaps fascism is less wedded to patriarchy than it is wedded to a certain martial attitude about whatever values it latches onto. That attitude might be summarized as ‘do what I say or I’ll stomp on your throat.’ What I mean is that patriarchy is everywhere, so don’t be surprised if you can see it in fascism, and don’t be surprised if it looks especially dark when wearing jackboots. Among the problems with Stanley’s attraction to left authoritarianism is that it wastes an opportunity to get at the real issue with fascism and perhaps enlist conservatives in the cause of fighting it, since guess what? Traditionally, conservatives have taken issue with fascism. That’s because fascism isn’t merely or mostly or even essentially about patriarchy and mythologizing older, agrarian eras. Fascism is also about trashing traditional institutions and consolidating power under a single authority – both things that conservatives tend to have a problem with. But why appeal to conservative hearts and minds when claiming their ideology is the fast train to fascism is a better applause line?”

Indeed, there are parts of the book where Stanley talks about a conservative political position or a Republican politician and tries to make a comparison with Mussolini or The Third Reich—with the latter comparisons being textbook exemplifications of Godwin’s Law. This is wildly uncharitable, to put it lightly, and would be like talking about a statement of policy by, say, Bernie Sanders or a common position of the Democratic Party and then trying to make a comparison with the mass killings of the communist Pol Pot.

One way to contrast fascism is by comparing it with liberal democracy. Principally, the rights and freedoms of individuals in a liberal democracy include equality before the law, free speech, freedom of religion, and freedom of assembly. Liberal democracies also have constitutions that circumscribe the powers of the government and thereby put restraints on their power. And because they’re democracies, liberal-democratic states are governed by the consent of the people—in other words, citizens grant political power to representatives via elections that are fair and free.

In liberal democracies, the rule of law governs not just the people, but also the officials who make up the government. Branches of the government, such as the executive, judiciary, and legislative branches, function independently of one another—in other words, there’s a separation of powers within the government, along with checks and balances. This also helps to keep governmental power from being concentrated in one place. In liberal democracies, a constitution also provides certain protections for minority groups, such as sexual minorities, religious minorities, ethnic minorities, and others. This way, a government cannot abridge or annul those rights, nor can a majority democratically decide to do so. So, for instance, a government cannot decide to revoke the citizenship of gays and lesbians, and an electoral majority cannot vote for a political representative who in turn revokes the right of a particular religious community to pray, worship, and assemble. And liberal democracies are also generally tolerant of the different cultures, religions, and political viewpoints that people within a state might have. As part of the right to free expression, liberal democracies ought to have a free press as well—the press, in other words, should not be controlled, censored, or unduly influenced by the government.

Being explicit about the foundational features of liberal democracy is important if we’re going to assess how well a society reflects these features—and the extent to which a government, leader, or political party might violate these features. In other words, a government, leader, or political party is authoritarian to the extent that these features are violated in some way.

An interesting question that arises when thinking about liberal democracies is whether a government can favor or promote a specific language, culture, religion, or tradition. Japan, for instance, is considered a liberal democracy, yet there’s a widespread sense that Japanese culture and tradition—and even the demographic makeup of the nation—should be preserved. Thus, if, say, nations like Poland and Hungary decide to follow suit and explicitly want to preserve their cultural traditions, demographic makeup, native language, and the like, this does not ipso facto stop them from being liberal democracies. To take another example, liberal democracies also have every right to exert their sovereignty and defend their own borders and set whatever immigration or refugee policy they wish. Should a liberal-democratic nation like Japan, or Australia, or Germany democratically decide to have a very restrictive immigration or refugee policy, for instance, they wouldn’t suddenly cease to be liberal democracies. When it comes to immigration and refugee policies, liberal democracy prescribes no particular view or policy—anything goes.

There are various ways that a government could violate the features of liberal democracy. And if so, then to that extent they would deviate from the ideal of liberal democracy. For example, to take two examples discussed by Stanley, the Law and Justice Party (PiS) in Poland, and, perhaps to a greater extent, Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orban and his party (Fidesz), have both been accused of politicizing the laws and methods governing judicial appointments. So, in these cases, it is quite reasonable to worry that these political moves have deviated from a liberal-democratic ideal. But either way, none of this is in and of itself tantamount to fascism, because fascism is a very particular manifestation of totalitarianism—with Mussolini and Hitler being the paradigmatic cases of fascist leaders.

As a bit of a case study, consider Hungarian president Viktor Orban’s response to the activism of billionaire George Soros. Is the immigration and migration position of Orban, a democratically elected leader, an expression of fascism or merely an attempt to guard his nation’s sovereignty and to reflect the democratic will of his nation?

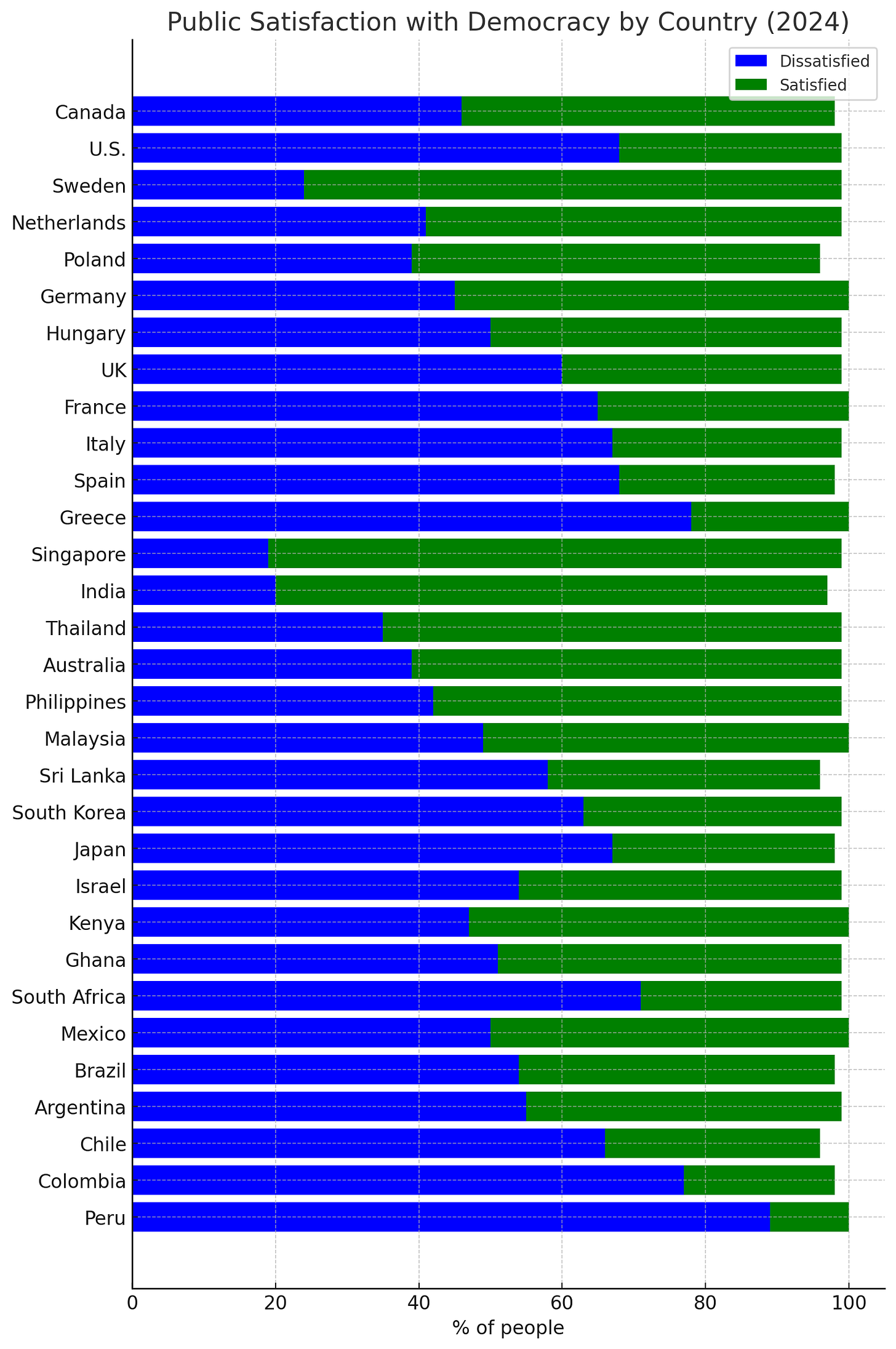

To be sure, there are some reasons to be at least a bit concerned about the future of liberal democracy. For instance, according to a poll by the Pew Research Center, large percentages of people—and in many cases, a majority of people—in several nations worldwide say they’re dissatisfied with the way democracy is working. Another recent poll by the University of Virginia Center for Politics found, shockingly, that 41% of those who support President Joe Biden, and 38% of those who support then-former President Donald Trump, reported that it was acceptable to use violence in order to prevent their political opponents from advancing their political agenda. The poll also showed the following results: 24% of Biden supporters and 31% of Trump supporters reported that democracy is “no longer viable”; 35% of Trump supporters and 47% of Biden supporters reported that the government should censor speech that they find offensive or discriminatory; and 47% of Trump supporters and 51% of Biden supporters reported that the other party was a “threat to the American way of life”.

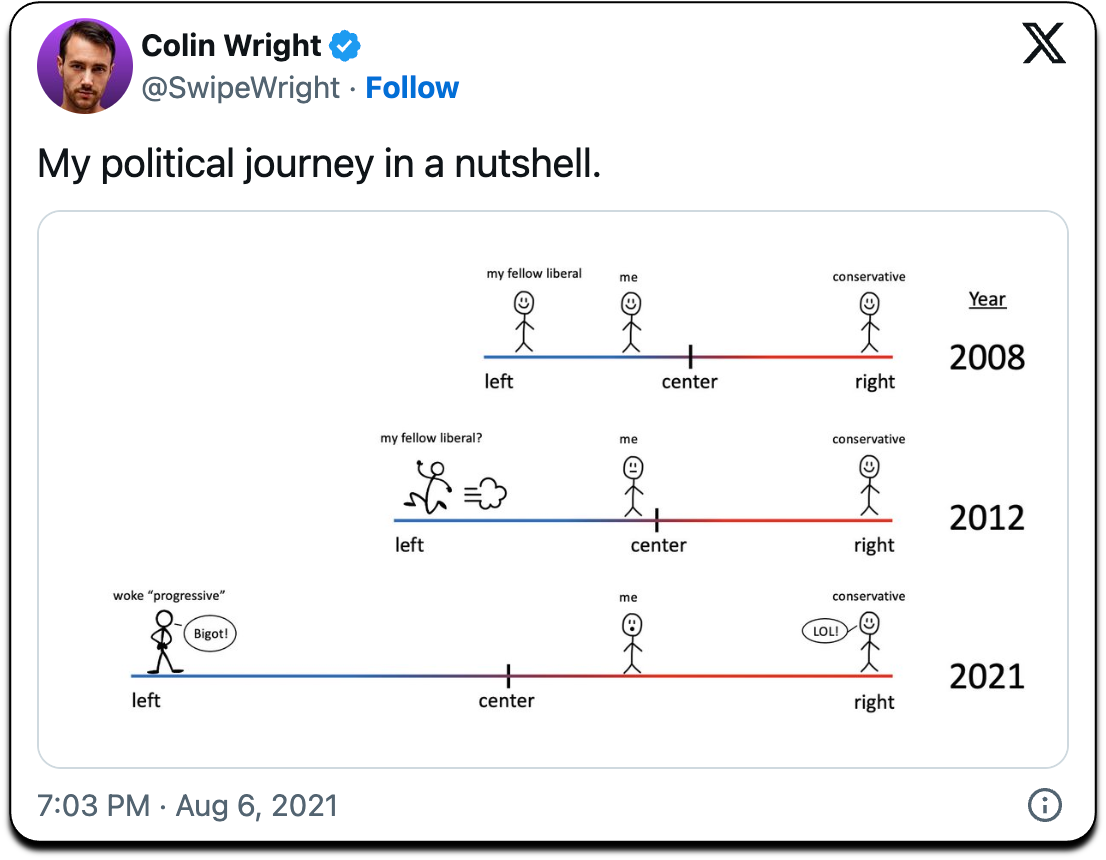

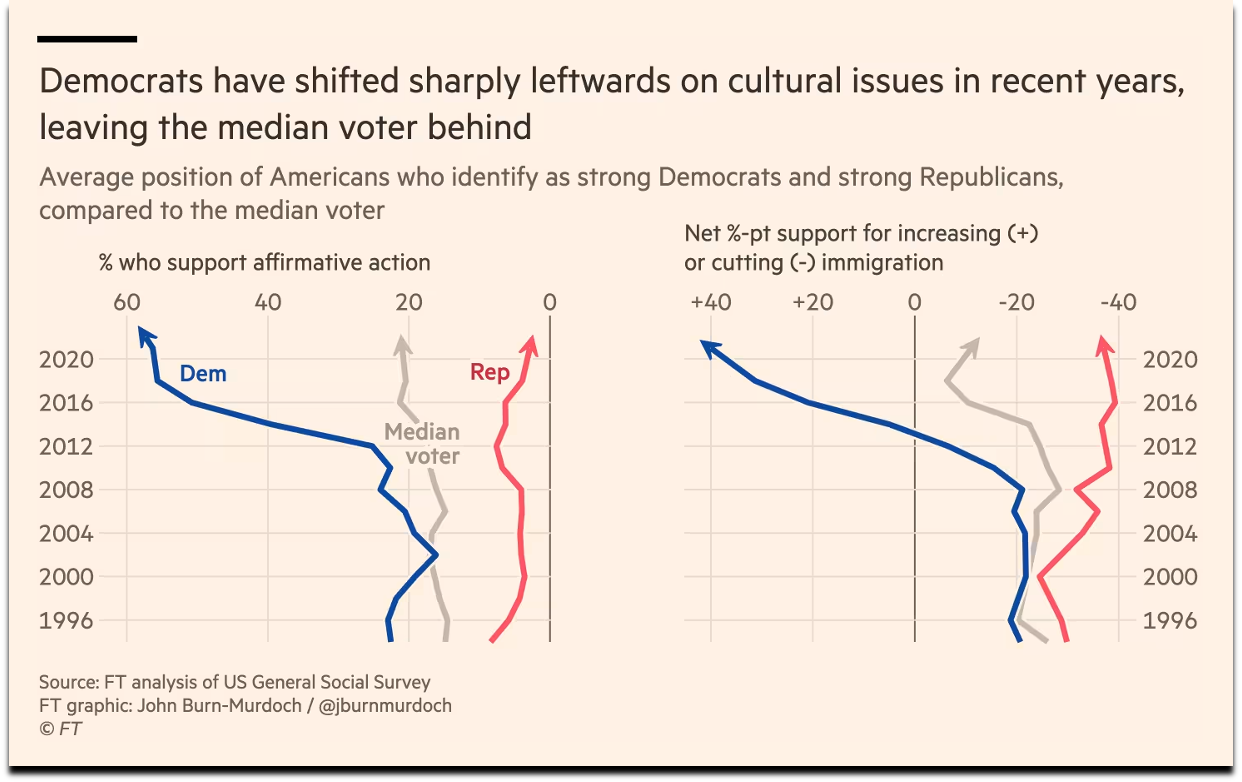

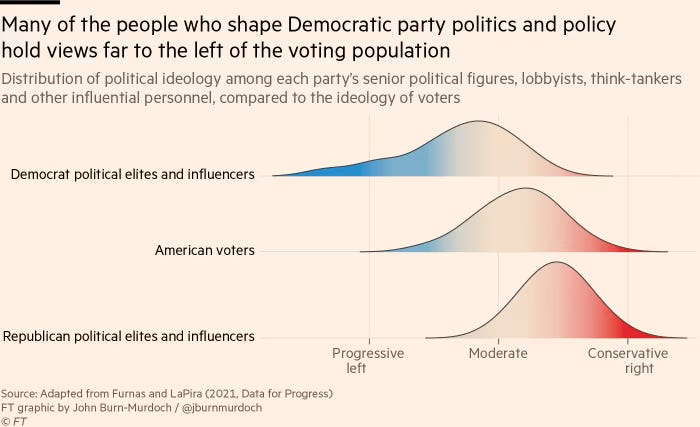

In the US, there are also other ways to test which ways the political attitudes of the electorate might be moving (assuming they’re materially moving in a significant way). For example, according to data gathered by the General Social Survey from 1996 to 2020, strongly identified Democrats have moved significantly to the left on cultural issues such as affirmative action and immigration policy, whereas there has been much less movement on those issues among both the median voter and strongly identified Republicans. Data from the thinktank Data for Progress also show that the elite figures in the Democratic party (prominent political figures, lobbyists, etc.) have political views that are much farther to the left than American voters as a whole; by contrast, elite figures in the Republican party have political views that deviate less from those held by American voters.

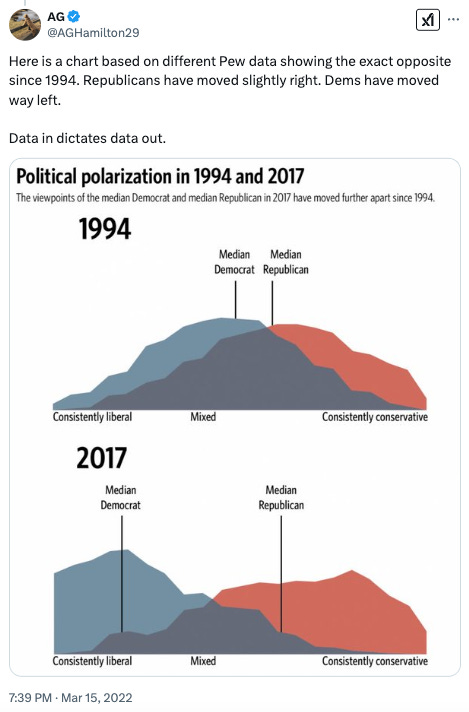

More generally, someone might think that Americans have been moving further rightward than leftward in recent years. However, the Pew Research Center reports that, from 1994 to 2017, the median Republican-leaning American moved about half a point to the right, whereas the median Democrat-leaning American moved 3-points to the left.

In the book’s epilogue, Stanley is clearly aware of the possibility that he might be overstating his case and being hyperbolic. But obviously this did not stop him from writing this book. In any case, you’d be better off looking elsewhere for a more impartial and accurate understanding of fascism.